April 3, 2017 – West Bend, WI – A sobering scene was unfolding at the beach when his ship docked after the trans-Pacific journey to Korea in 1950. With minimal ceremony, but with discretion and respect, fallen U.S. soldiers were being evacuated for burial onto a neighboring vessel.

Russ McCrimmon and his shipmates were at first confused by the scene that greeted them, but pretty quickly it was understood life as a U.S. Marine in Korea could be a grim business.

“It was the smell of death to us,” said McCrimmon. “I turned 18 before I got there, some guys were straight out of boot camp and there were a lot of young men that very soon became men.”

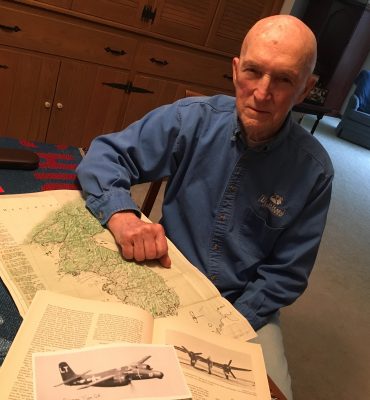

McCrimmon sat Marine-straight at his dining room table in West Bend, and spoke softly and clearly about his military experiences; a vintage map of Korea placed on the table in front of him helped tell the story.

Boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina in August of 1949 was the beginning of McCrimmon’s term of service but he didn’t get there without knowing a bit about the military beforehand.

One of McCrimmon’s uncles was in the Navy at Pearl Harbor, Dec. 7, 1941, during WWII.

Seventeen cousins served in various branches of the U.S. military; one of whom served as a guard at The Tomb of the Unknown at Arlington National Cemetery.

It was the inspiration of a friend in the Marine Corps in the South Pacific however, who inspired McCrimmon to enlist in the Marines at the age of 17, even before he had finished high school.

The GI Bill created after WWII allowed him to get credit for his senior year in high school in Batavia, IL. He graduated from high school and also earned a military GED certificate, making it possible for him to attend aircraft mechanic school, study at Quantico, and go on to be part of the HMR161 Squadron – the first helicopter transport squadron of any branch of the U.S. military.

He asked questions and learned about the testing of the new aircraft ejection seats. He participated in tests to 40,000 feet in a decompression chamber without a G-suit. Ask McCrimmon to tell you how to sew silk: he learned to make and repair silk parachutes and to pack them.

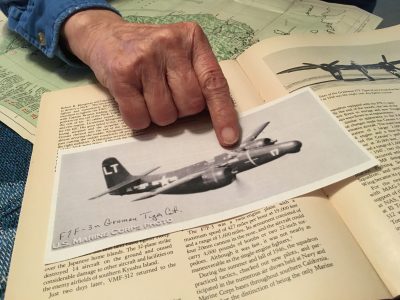

He also was one of the first to test ripstop nylon – the new material that became the standard for parachute construction. He rode in the back of the F7F-3n Grumman Tiger Cat – his name was actually hand painted in the cockpit.

He traveled extensively in Korea with his squadron, worked at the fronts and behind the lines, and after an injury spent two weeks on a hospital ship where he learned about the depth of compassion for the injured and dying soldiers.

With three months left of his tour of duty, he returned to the States to be in guard company at Great Lakes in Illinois. He and his family moved to the West Bend area.

McCrimmon is now 84 years old; he will turn 85 on the day after the Stars and Stripes Honor Flight. He is one of 90 veterans who will fly to Washington D.C. on April 8.

His guardian is his daughter Dr. Cathy Evans, who is a neuropsychologist working with military personnel suffering with PTSD, and this will be an opportunity to share his story with her in a very real way.

He is anticipating visits to the monuments, and is also hoping to at least drive by the corner of 12th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue where he used to play sandlot baseball with his friends from Quantico.

One of his boyhood friends died in Korea, and he’d also like to honor him by visiting the Black History Museum.

McCrimmon lives in West Bend with his wife Ann, and they have three grown children.