West Bend, WI – Over the last 15 years, Dave Bohn has been writing down memories of his childhood, growing up on the family farm just south of West Bend on Hwy P. He hopes his writings will preserve the often-overlooked stories of ordinary farmers and everyday farm life in rural Washington County during the Great Depression through the eyes of a local farm boy.

Remembering Pearl Harbor & Our Boyhood Treasure Hunts

When I was about 9 or 10 years old, our primary entertainment was to go to Rusco Creek, play ball with our cousins, or look for Indian arrowheads. Railroad tracks were also a big draw for us. My brother Tom and I and our cousin Jim Bohn would go to Rusco Creek (now known as Quaas Creek) and the railroad tracks near our farm. We would go for short walks on the wood ties, which were thick wood I-beams that the steel tracks were laid on. It was fun to walk fast, as we would skip one tie with each step. We would almost be running while skipping every other tie. Other times, we would walk on the iron rail to see how far we could balance on the rail without falling off. This was not always easy to do, as the rails had a slight mushroom shape to them.

I think there were 10 or 11 trains that ran each day on that track near our farm. It was the Northwestern Railroad track that went into Milwaukee and eventually connected to Chicago. These railroad tracks have changed, and a portion has now been converted to the Eisenbahn Trail.

There is a railroad trestle that runs over the creek. Underneath the trestle was one of our favorite places to be, as we liked to hear the trains pass over the trestle while we were underneath it at the creek.

There would be a loud rumble and the bridge would shake but we liked it that way. This is where we were on December 7, 1941—at Rusco Creek under the rail trestle with my brother Tom and our cousin Jim.

In a few days, it will be the 80th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and I still remember exactly how it all went that day. It was a Sunday, around noon, and there were patches of snow on the ground, but not enough to affect our walking. It was a sunny but cold December day, a good day for three boys to roam about. On that day, we heard the fire whistle blowing for about 10 minutes without stopping and we didn’t know why. This was an unusually long time for the whistle to blow. Normally, the fire whistle only blew about two minutes to signal there was a fire somewhere and the firemen should report to the firehouse.

We learned later the whistle signaled the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands. I imagine Mom and Dad would’ve put on the radio to find out what was going on. They probably put on the local radio station out of Milwaukee (The Journal WTMJ) and discovered that there was much damage to the ships in Pearl Harbor and the attack would lead the United States into WWII.

We were just boys then and continued to explore under the railroad trestle. Since we didn’t know what the whistle was for, we didn’t rush home. When we arrived home, we heard the news about Pearl Harbor. The fact we would soon be at war didn’t bother us boys much, as at that point, people were more worried about the Germans than the Japanese and the Germans could not reach the U.S. with their war equipment at that time. I do remember Mom and Dad were upset though, as they didn’t know what to expect. My brother Tom was 14 years old at the time, so while we weren’t quite at the age to go in the service, we were getting close to that age. Jim was a little older than we were and Jim’s brother, Robert Bohn, was 18 and enlisted in the Navy shortly after Pearl Harbor.

Tom, Jim, and I did a lot together. Jim came over almost every other day in the summer. When chores were done, we just roamed around a lot; never through fields that were planted, but through pasture land for cows that most farms had. We usually ended up at Rusco Creek.

It would take about 30 minutes to walk there. We went to the creek at all times of the year. In the winter months, we just looked at the creek and would look around for wild animal tracks. Sometimes we’d try to find firm ice and slide on it with our boots. Our boots were rubber galoshes that went over our shoes and up to our knees. They worked well for sliding but occasionally the ice wouldn’t be firm enough and we’d break through, water would go up over the boots, and we’d get wet feet. That would end our fun and then we’d make the walk home.

Rusco Creek was really our summer home though, as we spent many hours playing there in our younger days. Almost every day in the summer, we would fish for minnows to sell to the fishermen that came to the surrounding lakes, and then go skinny dipping. The creek was not deep enough for swimming, so we built a dam to make the water deeper. This we did with rocks from the creek and sod from the creek banks. This did not make the landowner happy and at times he would yell at us to get out. This would last about a day or two and we’d be back. It didn’t bother us too much as we were kids and he was good to tolerate us at all.

At the time I was growing up, the area around Rusco Creek was a cow pasture, so the grass was kept short and the creek was easy to get to. Now that farming has changed, this cow pasture has grown over with brush because the cows aren’t there, and it is too wet to farm.

Somewhere in the pasture land of most farms was a junk pile. There was no rural garbage pickup at that time, so you found your own place to dispose of your garbage. If the farm was adjacent to a railroad track, the pile ended up there. That way, the farmers didn’t use any of their own working land for garbage disposal. The railroad owned about 50 feet on each side of the track that wasn’t used, so it made a good dumpsite.

Every farm had a junk pile but they never got real big, maybe 10’ x 10’. It was mostly metal things that went into these piles. Old farm equipment made of iron was discarded in the railroad right of way. Because it was during the Great Depression, people just didn’t have much and farmers would repair what they could. If the item couldn’t be repaired, the farmers would throw it on their junk pile. My dad kept our junk pile near the unusable swampland on our farm. When a piece of equipment would break, Dad would haul it down to our pile and it would sit there until the junk dealer came out of Milwaukee.

I remember the junk dealer as being an old man and his name was Sam Jacobs. I think he immigrated from Russia, and he talked with a broken English accent. He’d come once or twice a year with a truck and a guy that helped him load. He pretty much took any metal pieces but primarily was looking for iron and lead. He also took paper and even rags that were used to make paper. He paid my dad a small amount for what he took. But times were bad, and any amount of money was helpful to my mom and dad. He would then, in turn, sell the scrap metal, paper, and rags to factories in Milwaukee.

By the time I was about 11-12 years old, WWII gave value to anything made of metal. The war changed everything. The United States and its allies needed metal and paper and that’s when I primarily remember the junk dealer coming around. The scrap iron was used in the war effort and remade into war materials and equipment. Small items were also recycled such as toothpaste tubes and tin cans. We would save our toothpaste tubes for the lead content in them, and we would turn them in at the local stores where they collected them. Just about any metal was recycled for the war effort.

When farmers had stuff that couldn’t be sold to the junk dealer, they would take it to the railroad tracks which were at the edge of their farmland because no one stopped them from putting their junk there. Back then, the farmers used the railroad tracks as their own personal dump. Anything they couldn’t sell and everything of no use went to the pile at the tracks. For young boys, these junk piles were like heaven. There were always treasures to be found on those piles, so they were great for us boys to explore.

There were two or three piles in particular that we liked to explore. We’d spend about an hour looking through the junk and trying to find things that interested us. These piles were not places our folks really wanted us to explore because they contained more or less garbage, but we did anyways. There was always discarded iron from lots of old buggy parts. We would find the iron that was in buggy axels and carry the axels back to our home, about one mile away. When the junk dealer came around, we would sell it to him. Mom and Dad would let us keep the money we made from this venture, so it was a good job for us to find the metal and sell it.

Old clocks always interested us. When we found one in a pile near the tracks, we would bring it home, thinking we could get it to work. We always thought we had parts for it, but when we got it home, we didn’t have what we thought we had, so we never got a single one to work.

We liked finding gears, too. I don’t know why we liked the gears. We didn’t know what we would do with them, but they looked interesting to boys. There were a lot of old wooden chairs on these piles too. There were lots of things made with metal, so it was always interesting to rummage through these junk piles.

Recently, our sons took my brother Tom and me to the railroad trestle. We’re in our 90’s now and Tom and I can’t walk down to the creek anymore.

Rusco Creek and the rail trestle we played under is on the Eisenbahn trail, between Rusco Road and Paradise Drive.

The creek looks different now, 80 years later, as there aren’t cows grazing there and keeping the grass under control. There is a lot of brush there now and it would be difficult to walk the route we did back when we were boys. But we could still see the creek from the trail and I was happy to see that people are still coming to this area of Rusco Creek and the train trestle to enjoy a pleasant October day.

Today there are no junk piles, as unused things are recycled or thrown in the landfill. No more treasure hunts for young boys.

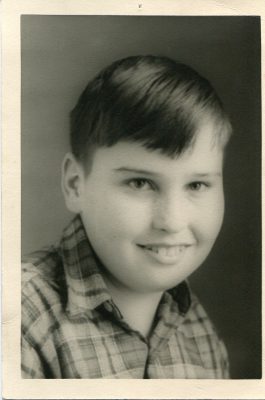

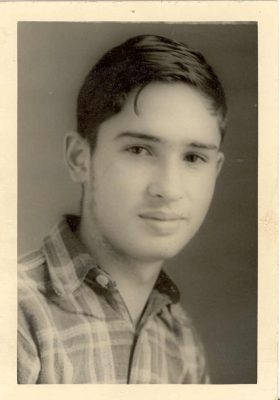

Submitted photos: Bonnie Bohn